Small Schools over time

2017 – Law no. 158 of 6 October

Measures to support and develop small municipalities: the National Assembly and Senate definitively approved the draft law no. 2541 which contains a series of measures aimed at small municipalities and for the redevelopment and recovery of Old Towns. In particular, art. 15 “lays down the Education plan for rural and mountain areas, especially with regard to the linking of school complexes located in rural areas and mountain areas to computerized services and the progressive digitization of the educational and administrative activities that take place in the same complexes.”

Measures to support and develop small municipalities: the National Assembly and Senate definitively approved the draft law no. 2541 which contains a series of measures aimed at small municipalities and for the redevelopment and recovery of Old Towns. In particular, art. 15 “lays down the Education plan for rural and mountain areas, especially with regard to the linking of school complexes located in rural areas and mountain areas to computerized services and the progressive digitization of the educational and administrative activities that take place in the same complexes.”

2012 – Experimental projects

Guidelines exist to strengthen the autonomy of educational institutions, also through a redefinition of aspects relating to transfers of resources to educational institutions, after the launch of an appropriate experimental project. For each educational institution, these guidelines define an “autonomy team” and, with reference to territorial networks of schools, a “networking team”. The maximum numbers of autonomy and networking teams are determined by reference to an MIUR-MEF decree issued every three years, based on forecasts of the demographic development of the school-age population.

Guidelines exist to strengthen the autonomy of educational institutions, also through a redefinition of aspects relating to transfers of resources to educational institutions, after the launch of an appropriate experimental project. For each educational institution, these guidelines define an “autonomy team” and, with reference to territorial networks of schools, a “networking team”. The maximum numbers of autonomy and networking teams are determined by reference to an MIUR-MEF decree issued every three years, based on forecasts of the demographic development of the school-age population.

2012 – Legislation for Digital School Centres (Art. 11 Law 221)

For schools working on the small islands, in the mountain municipalities, in areas inhabited by linguistic minorities, in areas at risk of juvenile delinquency or characterized by the substantial presence of pupils with special difficulties in learning and schooling, the regions and local authorities enter into agreements with the MIUR to establish digital school centres that are functionally connected to relevant educational institutes through the use of new technologies (Law no. 221/2012).

For schools working on the small islands, in the mountain municipalities, in areas inhabited by linguistic minorities, in areas at risk of juvenile delinquency or characterized by the substantial presence of pupils with special difficulties in learning and schooling, the regions and local authorities enter into agreements with the MIUR to establish digital school centres that are functionally connected to relevant educational institutes through the use of new technologies (Law no. 221/2012).

2009 – Presidential Decree no. 81 of 20 March

The minimum number of students needed to institute a class (15 pupils for the primary school) was raised, while multi-age classrooms (established in deprived areas and in the mountain municipalities) could comprise a number between 8 and 18 pupils. The institution of multi-age classrooms did not envisage lower thresholds in mountain areas, since this was a possibility granted precisely to schools in the most deprived areas. Consequently, the maximum threshold of eighteen students could mean the establishment of single multi-age classrooms in smaller communities.

The minimum number of students needed to institute a class (15 pupils for the primary school) was raised, while multi-age classrooms (established in deprived areas and in the mountain municipalities) could comprise a number between 8 and 18 pupils. The institution of multi-age classrooms did not envisage lower thresholds in mountain areas, since this was a possibility granted precisely to schools in the most deprived areas. Consequently, the maximum threshold of eighteen students could mean the establishment of single multi-age classrooms in smaller communities.

1999 – Presidential Decree no. 275 of 8 March, (Regulations on the autonomy of educational institutions)

“The modular division of groups of students from the same or different classes or from several years allows flexible management of the school calendar, the weekly and daily timetables, the division of the groups. Small mountain schools can adopt flexible solutions not only between different classes, but also between neighbouring complexes, to provide groups of classes for a certain number of hours per week and thereby relieving the discomforts of transfers”

“The modular division of groups of students from the same or different classes or from several years allows flexible management of the school calendar, the weekly and daily timetables, the division of the groups. Small mountain schools can adopt flexible solutions not only between different classes, but also between neighbouring complexes, to provide groups of classes for a certain number of hours per week and thereby relieving the discomforts of transfers”

1997 – Interministerial Decree no. 177 of 15 March

“Exceptions have been established with regard to the minimum limit of members for each section in schools and classes, or multi-age classrooms, only in the municipalities in the mountains and on the small islands, provided they contain at least six children. In lower secondary education, classes can be constituted that are unique for each year of the course, with a number of pupils less than the minimum values established, but in any case, more than ten […] in mountain areas, on the small islands or in areas inhabited by linguistic minorities. […] The minimum number of students is reducible up to eight on the small islands and in those mountain municipalities in situations of serious hardship because of the altitude of the villages, the orographic conditions, at a distance from the neighbouring schools, and the state of the communication routes.”

“Exceptions have been established with regard to the minimum limit of members for each section in schools and classes, or multi-age classrooms, only in the municipalities in the mountains and on the small islands, provided they contain at least six children. In lower secondary education, classes can be constituted that are unique for each year of the course, with a number of pupils less than the minimum values established, but in any case, more than ten […] in mountain areas, on the small islands or in areas inhabited by linguistic minorities. […] The minimum number of students is reducible up to eight on the small islands and in those mountain municipalities in situations of serious hardship because of the altitude of the villages, the orographic conditions, at a distance from the neighbouring schools, and the state of the communication routes.”

1996 – Law no. 662

“In the nursery school, the minimum number of members in each section remains fixed at fifteen children. This limit can be reduced up to ten for the sections operating in the municipalities in the mountains and on the small islands. In the elementary school, the minimum number of students per class is fixed, normally at fifteen children, reducible up to ten […]”

“In the nursery school, the minimum number of members in each section remains fixed at fifteen children. This limit can be reduced up to ten for the sections operating in the municipalities in the mountains and on the small islands. In the elementary school, the minimum number of students per class is fixed, normally at fifteen children, reducible up to ten […]”

1952 – Manifesto for a rural school

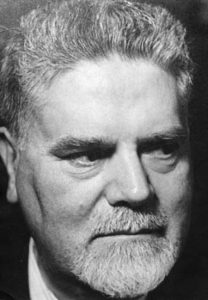

Roberto Mazzetti.

Roberto Mazzetti published the “Manifesto for the Rural School”, an intervention programme with which the educator proposed improvements to those elementary schools to be found in the Italian countryside..

1949- Toward the ‘multi-age classroom’

In the fledgling Italian Republic, the need was still felt for rural schools, so much so that the report of 8 April 1949 which discussed the results of the national investigation into the conditions of schools “brought to light the general desire on the part of the respondents to see rural schools grow and develop, allowing an autonomous elastic curriculum to meet their numerical and environmental needs, but also the characteristics of rural populations and the economy of the various zones.” The administrative revisions to country schools meant that in those years the outdated adjective ‘rural’ would gradually be replaced by the more technical term ‘multi-age classroom’.

In the fledgling Italian Republic, the need was still felt for rural schools, so much so that the report of 8 April 1949 which discussed the results of the national investigation into the conditions of schools “brought to light the general desire on the part of the respondents to see rural schools grow and develop, allowing an autonomous elastic curriculum to meet their numerical and environmental needs, but also the characteristics of rural populations and the economy of the various zones.” The administrative revisions to country schools meant that in those years the outdated adjective ‘rural’ would gradually be replaced by the more technical term ‘multi-age classroom’.

1946 – Constitution of the Italian Republic

The Minister Guido Gonella at the National Teaching Centre, 1950s.

“All citizens have equal social dignity and are equal before the law, without distinction of sex, race, language, religion, political opinion, personal and social conditions. It is the duty of the Republic to remove those obstacles of an economic or social nature which constrain the freedom and equality of citizens, thereby impeding the full development of the human person and the effective participation of all workers in the political, economic and social organisation of the country.”

Constitution of the Italian Republic. Art. 3

The second paragraph of art. 3 of the founding charter demands not only the equality of all human beings, but also the removal of the obstacles which prevent the full realization of the human person: attending the entire cycle of the elementary school cannot be a privilege, but a minimum condition of citizenship.

The Christian Democrat Minister Guido Gonella appointed a commission to study multi-age classroom school programmes, consisting of such contemporary authoritative figures of Italian pedagogy as Gino Ferretti, Carmel Cottone, and Giorgio Gabrielli.

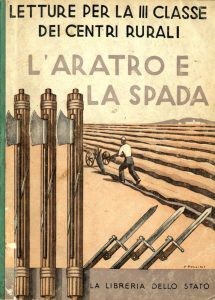

1931-1941 – School Charter

In the late 1930s, the rural schools attracted the attention of intellectuals and political authorities, who issued Royal Charter (RDL) no. 1196 of 20/06/1935, and Royal Charter no. 177 of 14/10/1938, both in perfect synchronization with the change wrought in February 1939 by the 9th Declaration which made an official distinction (in the programmes, legal systems and methods) between rural and urban schools as would subsequently be laid down in the School Charter commissioned by Giuseppe Bottai (1941).

In the late 1930s, the rural schools attracted the attention of intellectuals and political authorities, who issued Royal Charter (RDL) no. 1196 of 20/06/1935, and Royal Charter no. 177 of 14/10/1938, both in perfect synchronization with the change wrought in February 1939 by the 9th Declaration which made an official distinction (in the programmes, legal systems and methods) between rural and urban schools as would subsequently be laid down in the School Charter commissioned by Giuseppe Bottai (1941).

“The nursery school disciplines and educates the first manifestations of intelligence and personality, from the 4th to the 6th year. From the 6th to the 9th year, the elementary school is distinguished in the programmes, legal systems and methods, in both urban and rural areas; and gives a first concrete formation of character. From the 9th to the 11th year, the work school raises taste, interest and awareness of manual work through practical exercises systematically included in the study programmes.”

The Elementary Level, 9th Declaration, in the School Charter, 1939

1926 – Opera Nazionale Balilla

Pupils in the Balilla uniform

With the closure of the professional associations (Law no. 563 of 3 April 1926), the constitution of the Associazione nazionale fascista della scuola primaria, and the institution of the Opera Nazionale Balilla (Law No. 2247 of 3 April 1926) many ‘unclassified’ schools (477 rural and evening schools) became Scuole Rurali Opera Nazionale Balilla.

1925 – Athena Fanciulla

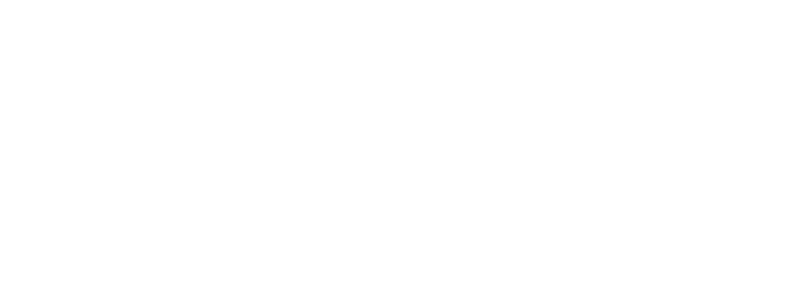

La Montesca school: classroom, Città di Castello (Perugia), 1920s.

The experiences of Villa Montesca and Rovigliano of the Barons Franchetti, those of the Ager Romanus and the teaching practices from Ticino of Maria Boschetti Alberti, had brought an entirely different character to rural school experiences with respect to that of the Risorgimento period.

In the pedagogical thinking of Giuseppe Lombardo Radice (previously explained in his book Lezioni di didattica, 1913) the rural school was able to compete with urban schools and overcome some of their limits: in the countryside the pupils’ subjectivity and spirit could be freer and more spontaneous. It was especially after the publication of Athena Fanciulla (1925), that the level of attention paid to the rural school grew in the political and scientific community that dealt with the educational field, to become the central theme of pedagogical reflection in Italy.

1924 – Study programmes for rural mixed elementary schools

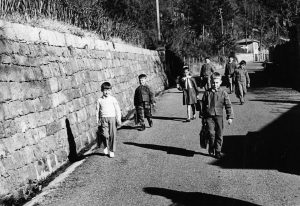

Scuola diurna di Marina di Palma (AG), anni Venti.

Publication of the “Study programmes for rural mixed elementary schools” (ordinance of 21 January 1924), according to which:

“[…] The Ministry wishes to facilitate the task of the mixed schoolteacher, by modifying some parts of the programme and suggesting adjustments to the timetable, although without any obligation to rigidly observe the indications of this ordinance.

Consequently, you will find attached a guidance framework for the timetable, in reference to the normal duration of the school year which will always consist of 180 lessons to be given in 10 months, as in urban schools, or in approximately 8 months, which might sometimes be more suited to the needs of those rural centres that require availability of infant labour, at certain times of the year, or where the climate makes the assiduity of pupils at school difficult if not impossible, in certain periods of the year.”

1923 – Multi-age classroom schools

The Tre Cancelli rural school in the Pontine Marshes, Latina, 1930s.

The need to adapt multi-age classroom schools to the renewed programmes and schedules, which took place on 1 October and 11 November 1923, was combined with the need to educate, as completely as possible, students with only one teacher who alternated between teaching classes I, II and III at the same time.

In drawing up the programmes, Lombardo Radice was one of the supporters of the merits of the multi-age classroom school where the variety of pupils was seen as an element of enrichment

1923 – Committee against Illiteracy

A rural school, photograph sent to Giuseppe Lombardo Radice in the 1920s by the Associazione Nazionale per gli Interessi del Mezzogiorno in Italia.

‘Unclassified’ schools, less burdensome for the State, had previously been run by the Opera contro l’analfabetismo, converted by the law of 31 October 1923 into the Comitato contro l’analfabetismo– the “Committee against Illiteracy”. Other institutions were also involved in the Committee such as the Gruppo d’Azione delle Scuole del Popolo, the Ente nazionale di cultura, the Società Umanitaria, the Comitato per l’Educazione del Popolo, the Consorzio Nazionale per l’Emigrazione e Lavoro, and the Associazione Nazionale per gli Interessi del Mezzogiorno in Italia.

1923 – The Gentile Reform

Portrait of Giovanni Gentile.

According to Royal Decree 2410 of 31 October 1923, schools were no longer to be divided into ‘rural’ or ‘urban’ on the basis of the number of inhabitants, or municipal tax revenues, but into two groups: ‘classified schools’ (in municipalities and hamlets with more than 40 school-age children) and ‘unclassified schools’ (run by institutions and cultural associations delegated by the State and opened in places with a number of pupils between 15 and 40, who only had a lower course available).

1911 – Daneo-Credaro Law

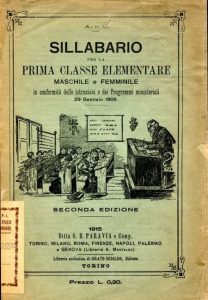

Primer for the 1st elementary class, 1915.

Presented for the first time in 1910 by the Minister of Public Education Edoardo Daneo, this law was promulgated the following year by the new Minister Luigi Credaro.

The law divided schools into two categories: those in provincial capitals, still directly managed by the municipalities; those in all other municipalities, under the authority of the Public Works Office. In this way, the State was directly involved in the organization and management of primary education in territories that were economically and socially deprived. The question of the school “with all classes together under a single schoolmaster” was dealt with in Title III, on “Restructuring of rural mixed schools and public lessons”, in which it stated that, under certain conditions, a teacher could teach the two sections of the same class at different times.

1906 – Measures for the southern provinces, Sicily and Sardinia

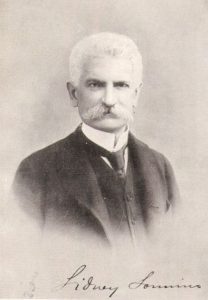

Portrait of Sidney Sonnino.

On 15 July 1906 a new law signed by Sidney Sonnino regarding “Measures for the southern provinces, Sicily and Sardinia” came into force, which allowed the establishment of third-class rural elementary schools fully financed by the State in hamlets and villages with at least 40 school-age children.

1882 – The Electoral Law

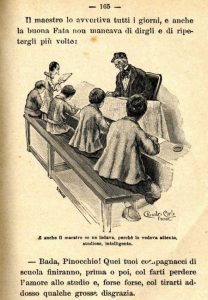

Pinocchio, by C. Collodi, inside illustration by C Chiostri, 1912.

In accordance with the 1882 electoral law, the right to vote was granted to anyone who had obtained the state elementary school certificate, under the terms established by the 1877 Coppino Law, and irrespective of the census conditions. With the result that education became the tool to acquire political citizenship, and literacy the lever for an approach to progress based on principles of desire and work (themes present in Cuore or Pinocchio), thereby foiling dangerous revolutionary demands.

1877 – The Coppino Law

Il figlio di Grazia, by S. Albini, inside illustration by G. Chiesa, 1870.

The 1877 Coppino Law was applied more strictly with regard to school attendance, punishing defaulting parents with fines, but remaining lax with the municipal administrations.

In the last twenty years of the 19th century, in the face of the shortcomings of the State in providing municipalities with means that would have allowed a proper dissemination of the ‘three Rs’, there were various initiatives to encourage attainment of the basics by the working classes, excluded until then from the cultural feast.

1873 – La scuola di campagna

Pleasant, new, instructive and moral tales by C. Percoto, “La scuola di campagna”, inside illustration, [1870].

1860-1870 – School Associations

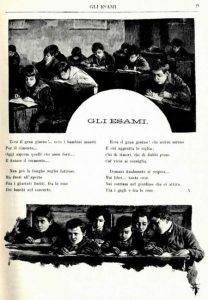

In città e in campagna: illustrated reading material for children, gathered by Cordeliaand A. Tedeschi, illustration by A. Ferraguti, 1898.

There was a spread of associations such as the Society of Education and Instruction (Pisa, 1866), the Society to Promote Public Libraries (Milan, 1867), the Ligurian Committee for the Education of the People (Genoa, 1876), and the National Association for the Foundation of Rural Nurseries (1867, which included such notable personalities as Terenzio Mamiani, Gino Capponi and Bettino Ricasoli) that proposed to establish a single school cycle of 5 or 6 years to assist children of both sexes of 3 or 4 years, and elementary schools in villages with fewer than 500 inhabitants.

1859 – The Casati Reform

In città e in campagna: illustrated reading material for children, gathered by Cordeliaand A. Tedeschi, illustration by A. Ferraguti, 1898.

With the Casati reform (1859), the term ‘rural school’ was introduced to distinguish between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ schools (in locations with a population of less than 3,000 inhabitants) matched by different teachers’ wages. However, this was a definition that paid no heed to the topographic, geographic, social and economic diversity that marked extra-urban Italy. Classes were put together on the basis of cultural knowledge, not necessarily on the basis of age. The only binding limitation was the minimum age of 6 years to be able to enrol at primary school.

1836 – The Guida dell’educatore

Portrait of Raffaello Lambruschini.

The Guida dell’Educatore (“Educator’s Manual” – 1836-1845), a journal directed by Raffaello Lambruschini, in describing the model schools of Hofwyl near Bern, focused on ‘rural schools’ for ‘poor children’ with a brief description of their characteristics. Italy was still far from such an approach: those who lived in the countryside, mountain areas and on the small islands did not awaken any concern regarding education among the upper echelons of the pre-Unification States into which the peninsula was then divided. Only in those municipalities with sufficient economic resources to pay for a teacher, often a cleric, did schools exist, attended not by the children of farmers, however, but by the children of the rural petit bourgeoisie.

Credits

- Historical and iconographic research by Pamela Giorgi and Irene Zoppi

- IT: Paolo Pantano

Bibliography

- PRUNERI, Fabio, «Pluriclassi, scuole rurali, scuole a ciclo unico dall’Unità d’Italia al 1948», Diacronie. Studi di Storia Contemporanea : Scuola e società in Italia e Spagna tra Ottocento e Novecento, 34, 2/2018, 29/06/2018, URL: http://www.studistorici.com/2018/06/29/pruneri_numero_34/

- MONTECCHI, Luca, I contadini a scuola. La scuola rurale in Italia dall’Unità alla caduta del fascismo, Macerata, EUM-Edizioni Università di Macerata, 2015.

- CALVARUSO, Francesco Paolo, Scuole rurali/pluriclassi e immagini d’infanzia del Novecento, in L. Vanni (cur.), Iconografie d’infanzia. Momenti, modelli, metamorfosi, Roma, Anicia, 2012, pp. 175-192.

Images from INDIRE Historical Archive

- Fondo Fotografico

- Fondo Antiquario di Letteratura giovanile

- Fondo Giuseppe Lombardo Radice

- Fondo Maestro Giuseppe Caputo